(continued from the previous episode…)

Now that we've dealt with repetitive code and escape sequences, here comes the actual meat of the problem: The indentation.

Indentation is a way to employ the 2D shape recognition capability built into the human brain in the service of understanding the code. If the indentation is broken, our innate 2D scanner switches off and we are left with having to understand the structure of the code the hard way, the way the compilers do. This off-switch of programmer's 2D scanner is used, for example, by the obfuscation technique that removes all the layout and present the whole program as a single line of code or as an ASCII art.

As far as code generation is concerned, there are two distinct problems to deal with: First, generator's source code has to be indented, second, the generated code has to be indented. As we'll see later on the two are interconnected in a subtle manner. However, for now, let's just note that the first problem is much more important to solve, as the generated code is mostly meant to be consumed by a machine and thus doesn't have to be particularly pretty.

Indenting of the code generator's source code is a hard problem and one that cannot be solved by technical means.

I am aware that when one asserts that something cannot be done he's just asking to be exposed as an idiot by someone who actually does it. However, let's consider my argument first:

The code generator and the generated program are two very distinct algorithms. After all, the first just concatenates some strings while the latter controls, say, a shoe factory.

That being a fact, their internal logical structure is going to be very different. Thus, if we want to use indentation to expose the logical structure of both, we are going to end up with two unrelated interleaved indentations:

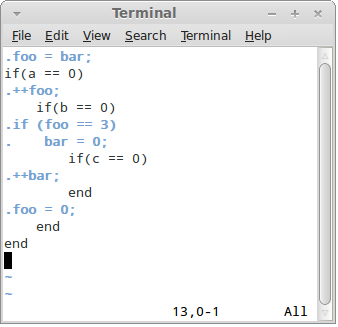

.foo = bar;

if(a == 0)

.++foo;

if(b == 0)

.if (foo == 3)

. bar = 0;

if(c == 0)

.++bar;

end

.foo = 0;

end

end

For all I can say, the problem is inherent to interleaving two distict programs and there's no way to twist it in such a way as to end up with a single indentation and yet preserve the ability to 2D-scan both programs.

So, let's accept double indentation as a fact. Is there a way to preserve 2D-scanability under such circumstances?

Think about it for a while! What we need is to see two different things in a single chunk of code…

And by now those with some psychology background should recall they have encountered something similar in the past.

And yes, you are right. It's the Necker cube!

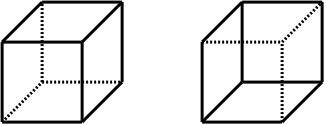

Necker cube is a single drawing that can be interpreted in two different ways:

From our point of view the most important property of Necker cube is that altough the observer can't see both cubes at the same time, he can switch between the two representations at will.

What we need to do is to achieve the same flip-flop effect with the doubly-indented code.

Switching between the two cubes happens by imagining that some lines are invisible (the dotted lines on the picture above). Sadly, the same trick doesn't really work with the ribosome source. You can try to imagine that the lines startng with a dot in the code sample above are invisible and focus only on the non-dotted lines. I expect it will give you hard time and the results won't be spectacular.

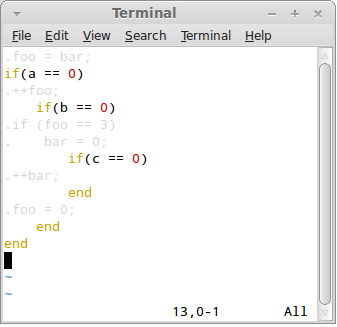

We can help our imagination though by using our colour preception capability. Here's the syntax-highlighted version of the code. Focus on the black code first, then try to switch to the blue code:

Have you been able to achieve the Necker-cube-like flip-flop effect? Have you seen black well-indented code first and blue well-indented code later?

Maybe not. It's not that easy. However — and I've tested it myself — if you spend an hour writing the code highlighted like that you'll get much better at switching between the two representations.

The syntax highlighting can be thought of as a computer-aided Necker cube effect. But why limit ourselves to plain old syntax highlighting? Surely, computer must be capable of doing more to help us.

When you put aside options that are technically unfeasible at the moment, like using our innate 3C recognition capability (control language on the foreground, generated language on the background), we can resort to yet more syntax highlighting.

Specifically, the computer can simulate the flip-flop effect for us.

If you install vim plugin for ribosome, by default you will be see the DNA files in black/blue colouring, as shown above.

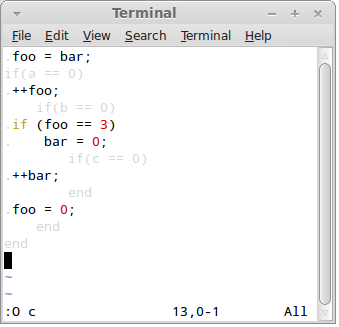

However, by pressing F3, the control language will get full Ruby syntax colouring while the generated language will be shaded, so as not to distract from the perception of the control language:

By pressing F4 you'll get exactly the opposite effect. Control language will be shaded and the generated language will be properly syntax-highlighted (you'll have to let vim know what language you are generating though):

By alternatively pressing F3 and F4 you are in fact generating the full-blown computer-aided Necker cude effect.

We'll return to the indentation of ribosome source later, but now let's have a look at the indentation of the generated code.

As already said, it's not that important, because it's something that will be processed by a machine anyways. There are two caveats though:

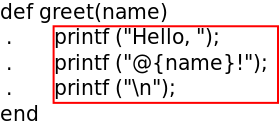

To understand the problem we are dealing with here, consider the following program:

def greet(name)

.printf ("Hello, ");

.printf ("@{name}!");

.printf ("\n");

end

.@{greet("Alice")}

.if (is_bob_present) {

. @{greet("Bob")}

.}

The output of such program — if done naively — would look like this:

printf ("Hello, ");

printf ("Alice!");

printf ("\n");

if (is_bob_present) {

printf ("Hello, ");

printf ("Bob!");

printf ("\n");

}

Note the mis-indentation in the lines 6 and 7! And with large non-toy programs, the problem will become ubiquitous — there rarely will be a line that's well indented.

If you run the above code with ribosome, the result will be correctly indented though. So what's going on here?

Before diving into technical details, recall how you deal with the same problem when you are editing code by hand.

While most of the time you spend editing individual lines of code, when the indentation is involved you often select a whole block of code and move it to the left or to the right as needed. Individual editors provide different means to make this operation easy to perform. For example, in most WYSIWYG editors selecting a block of code and pressing Tab moves the block to the right.

Can the code generator do a similar thing for us?

And the answer is, obviously, yes. The only thing we have to do is to stop thinking in terms of lines of code and rather think about rectangular blocks of code.

Technically, all string literals are trated as simple one-line block of code, while output of any embedded expression is treated as a rectangular block of code, whether is consists one line or mulitple lines.

The the following source code:

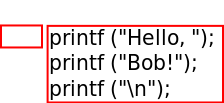

. @{greet("Bob")}

Can be graphically represented like this:

There's a simple literal block of 4 space characters on the left and a 3 line long block generated by function greet on the right.

Note how this system works in recursive manner. You can use it to properly indent pieces of code within your program, but your program as a whole can be treated as a single block of code and indented as needed:

def greet(name)

.printf ("Hello, ");

.printf ("@{name}!");

.printf ("\n");

end

def greetall()

.@{greet("Alice")}

.if (is_bob_present) {

. @{greet("Bob")}

.}

end

.#include <stdio.h>

.

.int main() {

. @{greetall}

. return 0;

.}

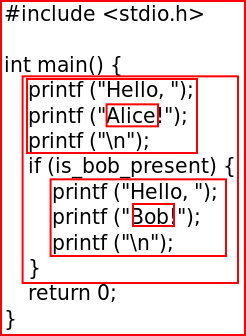

And here's the output, showing blocks of code as they were processed on different levels of the call stack:

All the above can be boiled down to a single leading principle: It's not the callee's task to manage the layout of the block being generated. Rather, it's caller's responsibility to place the block to the appropriate position.

What does that mean for the whitespace in the generated block? If every line of the block starts with four spaces, should we carefully preserve them, or should we rather say that it's not the callee's job to care about indentation and ignore the whitespace as random noise?

In ribosome I've opted for the latter choice:

Note how the whitespace on the left is not part of the generated block!

While this choice looks somehow arbitrary, it has not entirely consequence for formating of the DNA source file:

Given that any whitespace on the left will be ignored, we can add arbitrary whitespace in each function to re-synchronise divergent indenting between the control language and the generated language:

if(a == 0)

.i += 1;

if(b == 0)

.i += 2;

if(c == 0)

.i += 3;

if(d == 0)

.i += 4;

end

end

end

end

In lines 7 and 8, the control language is mis-aligned with the gererated language by 12 characters. Now consider what happens if we split the code into two functions:

def foo()

. i += 2;

if(c == 0)

. i += 3;

if(d == 0)

. i += 4;

end

end

end

if(a == 0)

.i += 1;

if(b == 0)

.@{foo}

end

end

As can be seen, the divergence doesn't exceed 4 characters here.

Finally, few words for the biologically savvy.

Of course, besides being an vague allusion to Ruby, ribosome's name refers to the molecular machine within the living cell, one that translates RNA into proteins.

And of course, ribosomes process RNA, not DNA.

So, if we want to stretch the biological metaphor further, ribosome tool plays role of both RNA polymerase and the ribosome itself. In fact, the tool works in two steps (invisible to the user):

April 27th, 2014